In 2023’s edition of Painting the Current Picture, the National Treatment Court Resource Center reported that across the United States, over 140,000 people were served by treatment courts in 2019 & 2020. From humble beginnings in the late 1980s to over 3500 hundred programs currently operating in every state in union is a testament to the success of the treatment court model, and the thousands of dedicated staff and organizations who make treatment court happen day in, day out. The treatment court model is one of the most well-researched, well-funded, and empirically backed justice interventions ever created. Participants who complete treatment court programs are less likely to commit new crimes, show significant reductions in the symptoms of substance use disorder, and higher level of recovery capital, compared to those who fail to complete the program, or those who get standard responses such as jail or probation.

As we enter National Treatment Court Month, in this 35-year anniversary of the treatment court model, it is important to acknowledge how far we’ve come, how many people we’ve helped, and, how much more we still must do. One of the biggest challenges facing the legal system, including treatment courts, is who is the program working for? At the most basic level, courts serving 140,000 people a year is a significant accomplishment, but, given that there are an estimated 8 million jail admittances each year, and that of those in jail, an estimated 70% have either a substance use disorder (SUD) or mental illness. There seems to be a huge pool of potential treatment court participants being missed.

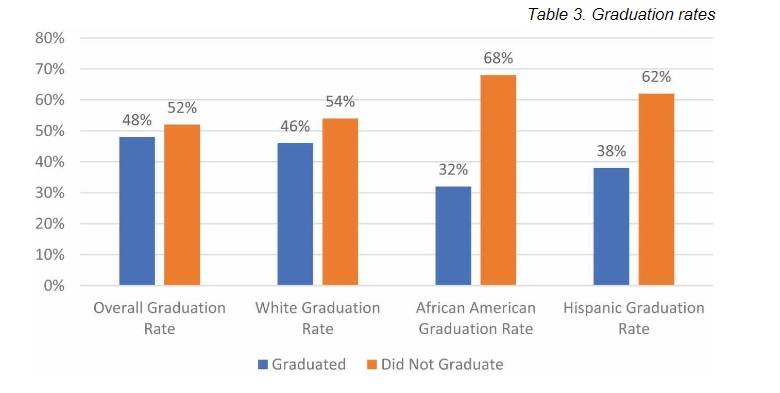

In addition, early scholarship suggested that treatment courts were failing to graduate Black and Latino participants at the same rates as their white counterparts, and while more recent data suggests that gap is narrowing, the fact remains that treatment courts are serving mostly white participants, in a legal system that disproportionately incarcerates and supervises Black and Brown individuals. Multiple recent studies have highlighted this disparity, generally, 70%+ of treatment court participants are white, compared to an average of about 40% of those in jails being white. Conversely, Black people make up almost 30% of the jail population, but less than 20% of the aggregate treatment court population. There are numerous reasons for this disparity, many outside the control of treatment court staff. Many decisions in the legal system also suffer from distributed responsibility, it’s rarely one decision that sets the course for an individual’s case processing, but many, small decisions by many different actors which cumulatively impact their experience, and racial disparities within the system. So how should treatment courts respond to these pre-existing disparities, and in compliance with the Adult Treatment Court Best Practice Standard (Standards) II, Equity and Inclusion, to ensure that their intake and eligibility policies and practices promote equity of access?

At American University, we’ve been working with treatment courts on issues related to equity of access for decades, and we’ve found a few areas where courts can increase equity of access and ensure that courts are serving all eligible participants. Firstly, courts should ensure that they are setting their criteria using evidence, which the Standards require that treatment courts serve High Risk and High Need individuals, and that’s it. Too many courts we’ve worked layer subjective criteria on top of these evidence-based standards. Some refuse to accept those with previous or current violent charges. The limited evidence we have shows people with violent charges do just as well in treatment courts, and a growing body of evidence suggests that those who commit violent crimes are less likely to re-offend than those with drug, property, or public order convictions. Evidence also suggests that most of the disparities in jail admissions can be explained by those charged with violent crimes. For treatment courts, serving those with violent charges is likely to reduce disparities in access, and keep communities safe, while saving significant costs associated with incarceration.

Treatment court should consider all the factors and not deny access to those who sell drugs. All the evidence we have suggests that almost all people who use drugs also sell some to support their habits. The decision to file a possession charge versus possession with intent to distribute, or other charges associated with drug sales, can derail someone’s access to treatment courts. Obviously, there is a significant difference between someone who is only selling for profit and who has no SUD (but they would likely not screen as High Need), and someone selling to support their habit, but blanket bans on those who sell or have sold drugs severely misrepresent the population of people who use, especially illicit, drugs.

Finally, courts should avoid broad exclusions which may unintentionally harm Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) participants, such as those without access to transportation, those without funds to pay program fees, those who have a “gang association” or those who “don’t seem motivated” etc. Part of the role of treatment court is to get people who have been struggling with addiction and its effect on their lives for a long time, back on their feet and re-integrated into their communities. For many, stopping using drugs is the primary need, and getting out of the gang, getting a job or financial security, access to a vehicle etc., are all goals that can be met after they stop using and start treatment.

Treatment courts have been serving their communities effectively for 35 years, but to ensure we are reaching all those who are eligible for our services, we need to be sure we’re not excluding people based subjective, or worse, racially biased, character assessments or characteristics. Treatment courts exist to serve those who criminal behavior is driven by substance use and / or mental illness, and it’s important that we don’t add additional, unnecessary, barriers to access.